Although it is probably correct to assume that the world is

innately varied, the world as we know it

is made of differences and distinctions. Among the many useful activities

performed by our very complex nervous system are the analysis and synthesis of

sensory data (including conceptions), the recognition of patterns, and the

comparison of those patterns with others stored in memory. Such processes,

together with others more obscure, enable us to make predictions about what

might occur in future, and to adjust both our expectations and our behavior

when things don’t go as we thought they would. Comparison is fundamental to our

ability to solve problems and adapt to novel opportunities. It is one of the

things we do best. It is also a habit and, therefore, a potential source of

difficulties.

When students of Zen read the Pali texts, we are bound to

notice that certain features of doctrine and practice differ from those

espoused by the Zen Ancestors and by our own teachers. The discrepancies will

strike us as odd because we are not just students of Zen but Zen Buddhists, after all. Enter the words “Zen”

and “Buddhism” into a search engine and you will bring up a list of items

numbering in the millions. What could be more natural than the linking of the

two terms? And yet, as we proceed with our studies, we may experience a growing

sense of tension between the two clusters of ideas. Uncovering the sources of

that cognitive dissonance is one of the great benefits of comparative studies.

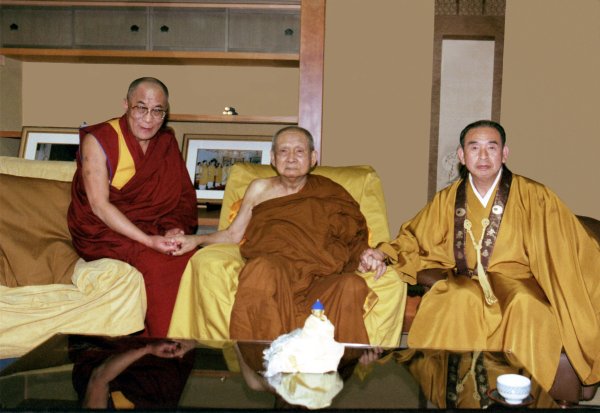

Followers of the Theravada call themselves Buddhists, as do

Mahāyanists and devotees of Mantrayāna/Vajrayāna, despite marked differences in

doctrine and practice. Are they justified in doing so? I am old enough to

remember the early days of Buddhist ecumenism, when South Asian monastic elders

sat at long tables with their Mahāyāna counterparts, uttering the platitudes of

unity and cooperation, only to mock and denounce in private the heretical views

and apocryphal scriptures of their “co-religionists,” while Chinese abbots were

heard to impugn the decadence and moral turpitude of the tantric practitioners,

influenced no doubt by residual antipathy to the Ching (Mongol) Dynasty.

Attitudes have changed. There is nowadays not only a good deal more genuine

tolerance, but a growing willingness to learn from each other. As a result, it

is no longer necessary to devote quite so much energy to ignoring the obvious

differences between the three main Buddhistic traditions.

In the past those discrepancies have been managed, or

papered over, by means of theories that can be briefly summarized as follows:

·

The principal innovations in doctrine and practice became necessary on account

of a gradual deviation from the Dharma. They are the product of reform

movements aimed at restoring Buddhism to its original purity.

·

Novelties in theory and practice result from changing methods and standards of

interpretation, or what theologians call hermeneutical strategies. These in

turn depend upon speculations about what the Buddha really meant when he said,

“X,” or what the words of the text

imply.

·The

successive revisions of Buddhism are in fact improvements, in the manner of

free software upgrades. Thus, the Deer

Park discourse can be thought of as the Beta version

and the Three Turnings of the Wheel as Buddhism 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0.

·

A closely related rationale is that of Skillful Means (upāya), according to which the Buddha taught a great many diverse

things (sometimes simultaneously!), all of them appropriate to the needs and

capacities of his listeners. The computer-literate can think of these as

programs designed to run on the Śrāvaka, Pp/Madhamika, Yogacara and

Tathāgatagarbha platforms respectively.

·

Finally, there are tales according to which certain early texts (recall that the Buddha’s words were not

written down) were hidden for the purpose of being retrieved later, when a

more intelligent and spiritually evolved audience could fully appreciate their

deep meaning (recall that, according to

the doctrine of the decline of the Dharma, people’s faculties only deteriorated

from the Buddha’s time onward).

The common element in most attempts to reconcile the

inconsistencies in Buddhist teaching and practice is the assumption that the

Nikāyas, the Prajnāpāramita literature, the Extensive (vaipulya) Discourses, and the philosophical treatises are various

expressions of what is essentially

one thing. The limitations of such a view should be obvious. It is a bed of

Procrustes, requiring a constant labor of excision, whereas we should be

striving to be inclusive. “Original” and “pure” are words beloved of

fundamentalists and zealots. It is our obligation as scholars to examine the

details of each Buddhistic teaching for what it is on its own terms, and

evaluate each on its own merits, as a unique cultural artifact perfectly

expressive of its time, place and culture.

We are less likely to be broken between the Scylla of

ideology and the Charybdis of fact if we treat the main Buddhistic religions as

we do the Abrahamic, that is, as a group whose members share varying amounts of

genetic material, and therefore bear more or less of a family resemblance to

one another. In the case of Judaism and Christianity, the latter is

identifiable as a descendant of the former, but no one would mistake the one

for the other. The same kind of genetic relations hold for Early Buddhism, the Great Vehicle

so-called, and the Mahāyāna’s esoteric offspring, Mantrayāna and Zen.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Feel free to kibbitz or send me a personal message via this box. Comments will be moderated.